Consistency, causal and eventual

In some previous blog post several consistency models were briefly described as well as what do they mean in terms of database transactions. With the following writing, I would like to further remove white knowledge gap and explain in simple terms some other well-known consistency models, such as eventual and causal. These are much more common within distributed systems rather than traditional databases, though, at the present time there is little difference between the two.

Sequential consistency

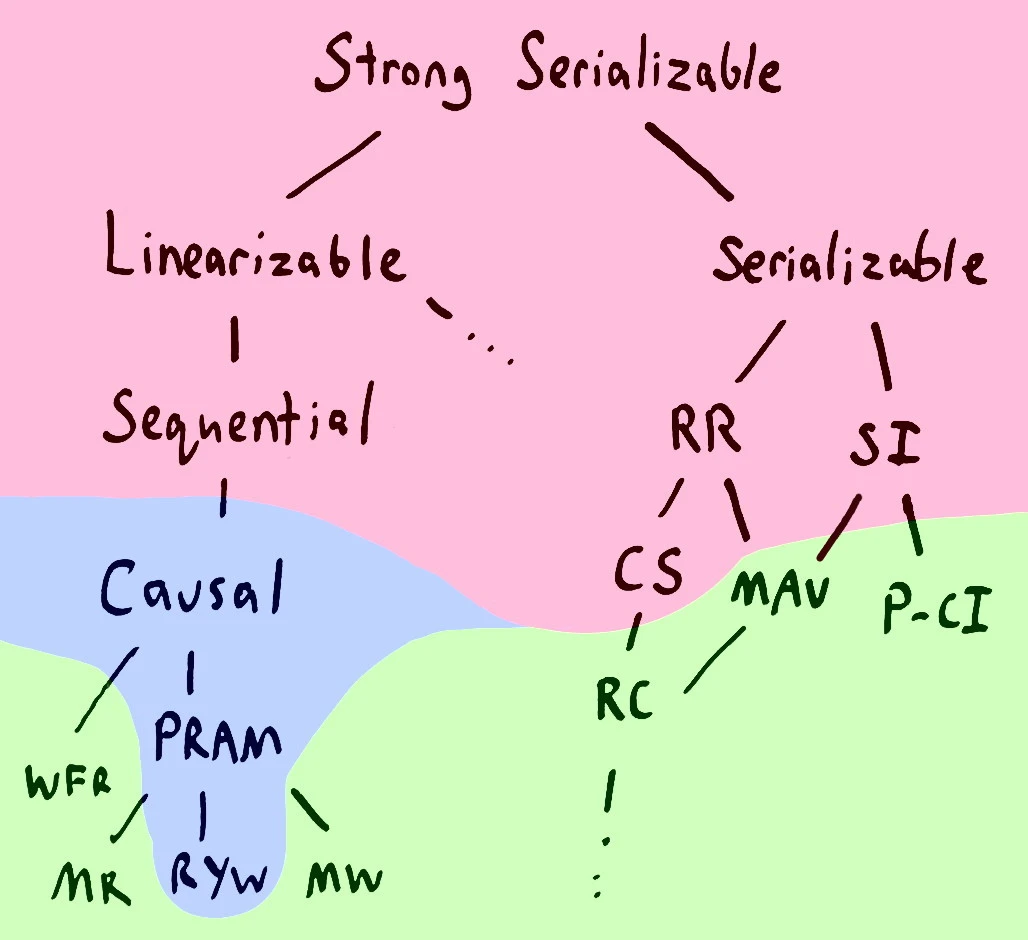

Let’s recall that last time we’ve coveded consistency models that followed right path:

So, we’ll assume that serializable model descendants are not that scary as they are for the first time. Today, sequential consistency model (left path of the image) lineage would be unveiled.

But first, let’s make ourselves familiar and comfortable with the sequential model itself. It was defined by Lamport as a property:

the result of any execution is the same as if the reads and writes occur in some order, and the operations of each individual processor appear in this sequence in the order specified by its program.

Well, I’d like to have a more intuitive explanation. Sure, if one devotes enough mental efforts this statement could be easily deciphered, but humans are inherently lazy (at least I am), so let’s try to rewrite its definition (or better, redraw!) for easier understanding.

Different resources on the web use different examples to explain sequential consistent systems. Here, I want to emphasize that it’s sufficient to imagine some abstract clients (independent) and some shared resource they all have access to. For example, CPUs (or threads) could be our clients and RAM (or register) could be shared resource. Also, some distributed system (say, HDFS) could be shared resource and Alice and Bob applications could be our clients. But it’s basically just some independent workers and a shared resource.

Also, all that consistency models are a just fancy way to describe a contract between the system and its users: what users can expect from the system during an interaction, what state does system have to be in.

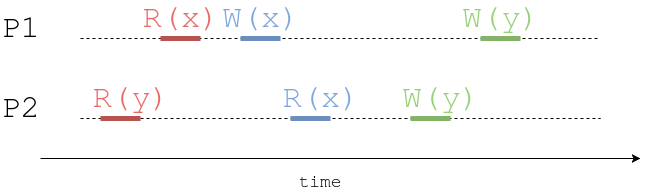

Okay, let’s imagine there are tho processes (P1 and P2) who talk to a system. The first process does red read R(x), then blue write W(x) and green write W(y). The second process performs red read R(y), then blue read R(x), then green write W(y).

If our system claims to be strictly serializable, then it has to appear as a single global place with all operations appear to all processes exactly in their global order. Probably, such system would need global wall clock time (which is pretty hard to obtain).

What does system guarantee? It says process’s P1 red read happens before its blue write, and its blue write happens before green one. It also says that process’s P2 red read happen before process P1 red read, i.e. all events are totally ordered. Pretty strong guarantee.

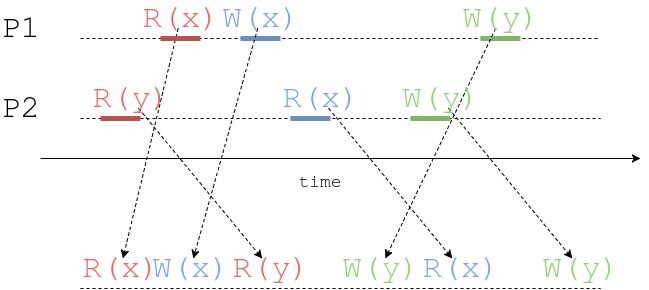

Now let’s imagine systems says it’s only sequential consistent. What does change? Well, it still guarantees that P1 process read happen before its writes, and blue write occurs before green. The same is true for the process P2. So, every process’s operations order is preserved. But the subtle difference is that total order is not guaranteed: the system may interleave operations as it likes:

Every process operation order is preserved (as per definition), but the real order is not guaranteed. Some operations may even look like to happen in the past! So, sequential consistency tells every process that its operations would appear in the order they’re issued. Of course, once an operation is finished it’s visible to all clients. Being sequential consistent allows system some flexibility in interleaving different process’s operations. It’s easier to implement and there is no global clock requirement.

Causal consistency

Hope it’s a little more clear now about sequential consistency. Moving on. What if we relax our requirements? Then we have eventual consistency model. It guarantees less but could be more performant and simple to implement.

In that case, we have a pretty simple guarantee: only causal operations appear in order. And they appear in order for all clients. However, other operations can be seen by different clients in arbitrary order. By comparison, sequential (and strict) consistency requires all operations committed should appear in the same order. So, we’re relaxing this constraint to apply for only causal realted operations.

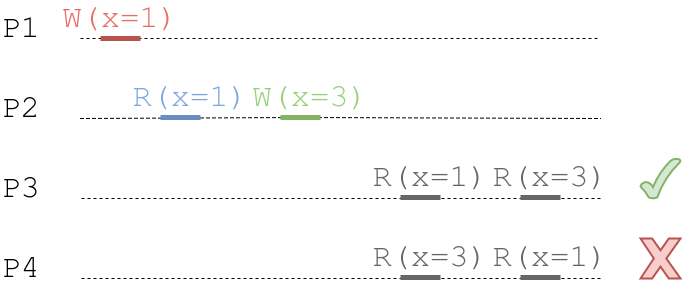

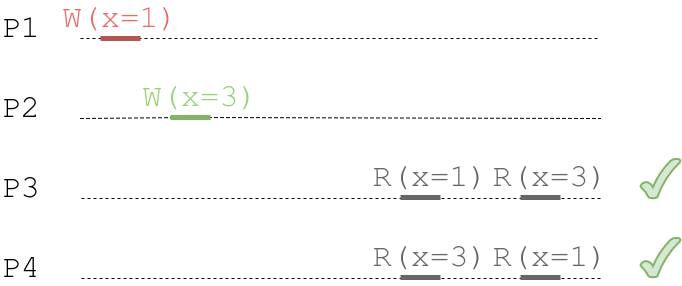

Here’s illustration of this concept:

The first process writes value 1 to x, then the second process reads from x (we suppose it reads value 1), possibly performs some computation and then writes value 3 to x again. These operations (write/write) are causally related, and hence their order should be the same for all processes. Now, we have other processes who try to read from x. The third process first reads 1, then subsequently reads 3. All is fine since the correct order is preserved. The fourth process first reads 3, and then 1. This is a violation of causal consistency. Within a system with causal consistency guarantee, P4 history is impossible.

However, if operations are not causally related, users can see different orders for them. In an image below, two processes write different values to x, and since they’re independent, there is no order guarantee.

A more human example could be for comments and replies. Consider these posts:

- Oh no! My cat just jumped out the window.

- [a few minutes later] Whew, the catnip plant broke her fall.

- [reply from a friend] I love when that happens to cats!

Causality violation could result someone else screen would have:

- Oh no! My cat just jumped out the window.

- [reply from a friend] I love when that happens to cats!

- Whew, the catnip plant broke her fall.

The third message is causally related to the second. In causally consistent system order (original 2 -> 3) must be preserved.

It has been proved that no stronger form of consistency exists that can also guarantee low latency (see Prince Mahajan, Lorenzo Alvisi, and Mike Dahlin, “Consistency, Availability, and Convergence,”).

Eventual consistency

Simply put, eventual consistency guarantee is “given no updates (writes) all clients will see exactly the same state of a system in some time”. So, if we stop doing new writes, the system will eventually converge to some consistent state. This is a very weak constraint that is (probably) simpler to implement and could be very performant.

Okay, we’ve covered almost all abbreviations from our top image, and only a couple left: PRAM, WFR, MR, RYW and MW. Let’s decipher those.

These refer to so-called session guarantees, client-centric (strict and sequential, by comparison, are data centric). So, nothing is guaranteed outside a “session” (some client set of operations - context).

Monotonic reads (MR) says that once you read some value, all subsequent reads will return exactly this value or a newer one. A notable example is reading some value from a system, then possible due to network issues and partitions, one could get stale (old) read. Monotonic read systems prevent that scenario.

Monotonic writes (MW) requires all your writes become visible in the order they were submitted. One can be sure that the system won’t change the ordering. Consider you write +$50 followed by +10%. With monotonic writes, you can expect that applying those operations to an account with $100 would result in $165 ($100 + $50 -> $150 + 10% -> $165) rather than $160 ($100 + 10% -> $110 + $50 -> $160).

Read your writes (RYW) requires that whenever a client reads a given data item after updating it, the read returns the updated value. Simple.

Pipelined Random Access Memory (PRAM) ensures all operations from a single process are seen by other processes in the order they were performed as if they were in a pipeline. It’s a combination of previous three models.

Writes follow reads (WFR) says some write operation that follows some read operates on that or more recent value. Put it in transaction terms, if a client sees an effect of transaction T1 and commits a transaction T2, then some other client observes an effect of T2 only if it observes an effect of T1.

These guarantees realize eventual consistency.

Conclusion

The last question that could be answered is “what are those colored areas in our guide picture?”. In short, red area systems could not be “totally available” (because of network partitions and else), while green ones could. They’re called “highly available” because of their weak guarantees. Blue area is for “sticky available” systems (whenever a client’s transactions are executed against a copy of database state that reflects all of the client’s prior operations, it eventually receives a response). More details could be found in seminal Peter Bailis paper.