Hybrid Logical Clock (HLC)

The notion of a time plays very important role in distributed systems. But, why do we worry so much about time? Perhaps, it’s pretty natural and easy for us humans to reason about everything with some sort of “time” in mind. As a programmer (and human) we are implicitly implying ordering on events, and it’s pretty convenient to have a notion of past, future, and present.

Time in distributed systems

Imagine yourself writing some program. How easier it is to reason about it running on a single computer rather than on a bunch of communicating devices? However, some problems are to be solved with a clustered distributed setting and one has to deal with it.

The particular important problem is sort of “synchronization” between different machines. How to do that? What about events that flow through the system?

Ordering

When I write some program (or application) I like to think commands are executed in order: that is, the first statement is executed before second one, and the third one is executed after it. See, there is a notion of time: statements (or events) have some ordering. Having such property is very comfortable and allows to write programs more easily. To better illustrate it let’s imagine, there are no guarantees that statements I’ve written would be executed in predefined (and known apriori) order. How do I reason about my program then? The whole program needs to be written in a totally different way to work around absence of total ordering property.

With a distributed systems we have to deal not with total ordering property, but partial ordering. In simple language, both total and partial ordering on events say that:

- If

ahappened beforebandbhappened beforec, thenahappened beforec(transitivity) - If

ahappened beforebandbhappened beforea, thenaequals (or, is)b(antisymmetry)

The difference between them is that for total ordering we can say for all events that “either a happened before b or b happened before a”. For partial ordering, we just don’t guarantee such relationship (something preceded something else) exist. We don’t compare them. Another useful explanation is offered by Tikhon Jelvis on Quora.

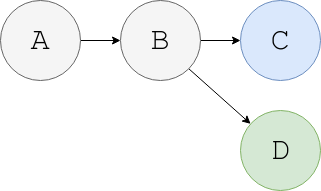

Another example is git branches: consider we have git history like this:

Here we say that A -> B -> C events have a total order. Same is true for A -> B -> D. But, there is no relation between C and D commits and so, we say A, B, C and D have only a partial order.

This is why we need a notion of time: it allows us to have order, it serves as a source of order. For example, if one is able to assign wall clock timestamps to different commits in the previous example, then all events will have total order because timestamps allow us to relate (compare) events!

Clocks

When dealing with distributed system we can imagine different scenarios, regarding time:

- We have access to perfectly accurate global clock

- We have access to imperfect local clock

- We don’t have access to any clock

The first scenario allows as to assign total ordering across all machines. This is what Google’s Spanner does with its TrueTime: make sure each node clock is accurate enough so timestamps from different nodes could be compared. It then solves some problems and simplifies system design.

The second scenario is a little more relaxed assumption that says we can have a total ordering on a local node by assigning timestamps, but events for the whole system can’t be ordered by using them. It is a much more plausible assumption and is closer to the real world.

Third one rejects the idea of having a physical time (no clock) and instead uses logical. Here we can order events across the system (to some degree, depends on communication latency), but there is no notion of real time, hence no timeouts, etc. It’s used to track causality.

Logical clocks

Let’s start with Lamport clock. Basically, it is just a counter that gets increased on:

- the process performs something

- the process receives message with counter from another process

It defines partial order, but has some caveats: if a happened before b, then timestamp(a) < timestamp(b). However, the converse is not true: events that are not causally related (no communication happened in between), then we can’t say anything about their ordering.

Vector clocks is an extension that instead of simple counter uses a vector of counters, one per node. It works like this:

- on operation local counter is incremented

- on message receipt each element is updated according to

max(local, received), local is incremented then

Vector clocks are more advanced that Lamport since they’re able to identify concurrent events (useful property due to network partitions). The downside is that it requires storing N clocks, where N is a number of nodes in a system.

In short, while Lamport logical timestamps give us e happened before f => lc.e < lc.f guarantee, vector clocks give e happened before f <=> vc.e < vc.f (note direction, it’s both-sided). A little more detailed explanation is offered in this blog post.

Hybrid clocks

Now, what if we combine both physical and logical clocks? Can we have a better way to order events? It seems that answer is “yes” as Logical Physical Clocks and Consistent Snapshots in Globally Distributed Databases paper demonstrates.

Recall that physical clocks are sometimes used to order events based on timestamps. However, there is some problem with real world physical clocks: it’s impossible to have all nodes to be in perfect sync. Even with Google’s TrueTime API (let alone NTP), there is uncertainty interval during which events can’t be ordered. One simple solution to that is to simply wait for this uncertainty out, it’s a way Google Spanner went. While TrueTime limits uncertainty window to less than 7ms, NTP can introduce 100-250ms intervals and too long waiting would limit performance.

As a side note, using a physical time to order events is a subject to other problems such as leap seconds and non-monotonic updates to POSIX time that could turn time backward, and generally, could introduce anomalies.

Hybrid logical clock preserves the property of logical clocks (

e happened before f => hlc.e < hlc.f) and as such can identify and return consistent global snapshots without needing to wait out clock synchronization uncertainties.

HLC was designed to provide one-way (as with LC rather than VC) causality detection while maintaining the clock value close to the physical clock, so one can use HLC timestamp instead of a physical clock.

Basically, using pretty clever algorithm and clock representation, it achieves

- one-way causality detection,

- fixed space requirement,

- bounded difference from physical time.

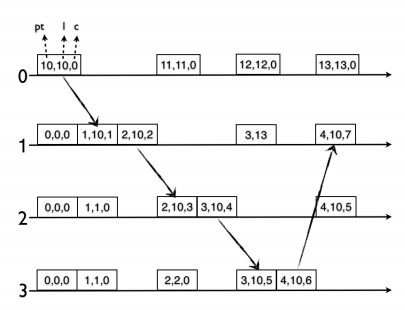

Paper describes clock that consists of three parts:

pt, for physical timel, logical, holds maximumptheard so farc, captures causality

It then combines them into NTP compatible 64-bit integer: pt is rounded to 48-bits when l is assigned and 16 bits are reserved to c. Once a 64-bit timestamp is needed, l is just concatenated with c. It serves as a drop-in replacement for physical clock timestamp.

Experiments (described in the paper) show that such algorithm and clock representation is pretty resilient to both stragglers (nodes with their physical time in the past) and rushers (in the future). It also self-stabilizing and is able to tolerate NTP clock corrections (though it has the rule to ignore some messages). Follow the paper for the details.

Summary

To cite the paper:

Since HLC refines LC, HLC can be used to obtain a consistent snapshot for a snapshot read. Moreover, since the drift between HLC and physical clock is less than the clock drift, a snapshot taken with HLC is an acceptable choice for a snapshot at a given physical time. Thus, HLC is especially useful as a timestamping mechanism in multi version distributed databases (MVCC).

To conclude, HLC combines the benefits of logical clocks (LC) and physical time (PT) while overcoming their shortcomings. HLC can be used in place of LC and is substitutable for PT in any application that requires it. HLC is strictly monotonic and, hence, can be used in place of applications in order to tolerate NTP kinks such as non-monotonic updates.